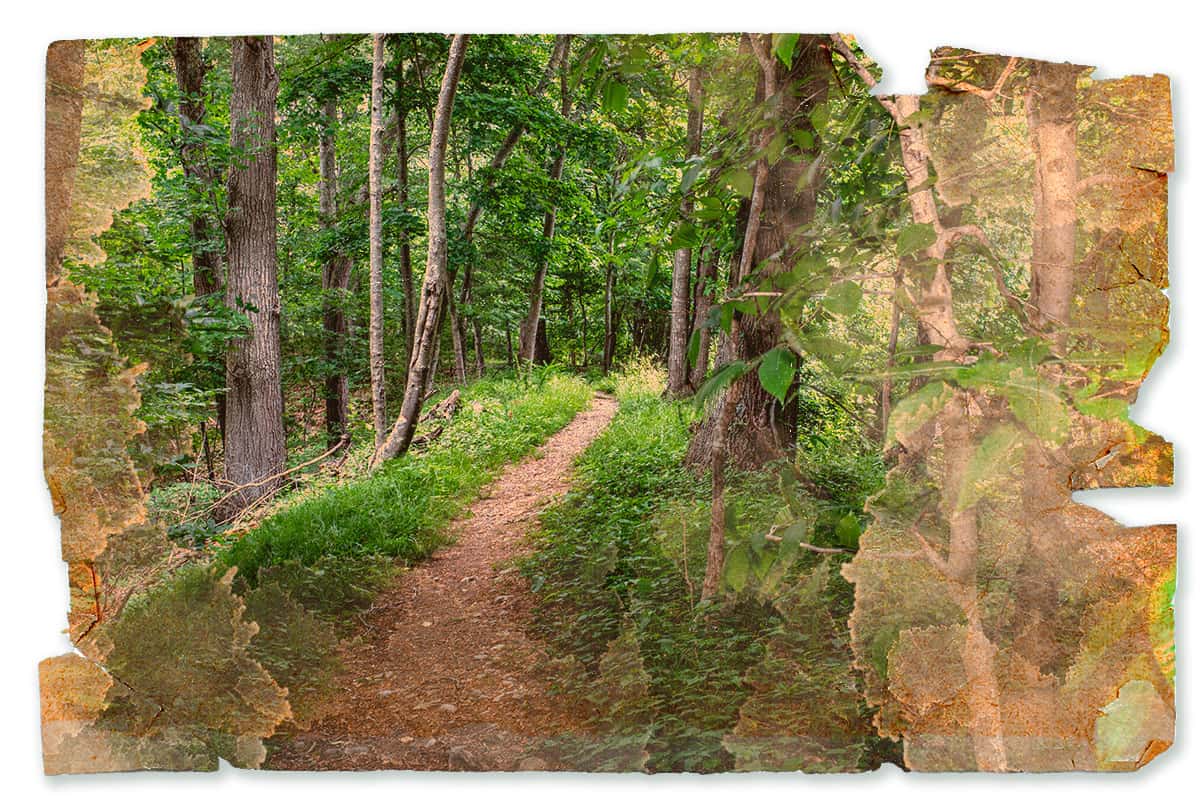

"Away from Hingham’s busy streets, are peaceful parcels of land where the only sounds are from birds and the soft breezes that flow through the trees,” says Don Kidston, a board member for the Hingham Land Conservation Trust. “Twisting trails lead through woods, along small streams, and uphill to rocky outcrops with views of blue skies and bright white cumulus clouds. Trails continue past old stone walls to open fields, with benches to sit on and perhaps observe deer and nesting birds while absorbing the peaceful sights, sounds, and feeling of the natural surroundings.”

The Hingham Land Conservation Trust, a private non-profit conservation organization, is marking its 50th anniversary this year. The group is marking this milestone by celebrating its history and launching programs for the decades ahead.

In the 1960s and 70s, town and community leaders in Hingham took steps to help preserve the town’s meadows, hills, wetlands, and forests, including creating the town’s Conservation Commission. At the time, environmental concerns were growing nationwide about pollution of land, air and water (the Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1970 and the first Earth Day “Teach-in” event took place that same year).

Locally, the opening of the southeast expressway in 1959 made the commute in and out the city easier, and many Boston-area residents started looking down the coast to towns like Hingham and all the open, buildable space with longing eyes. If small towns were to retain their natural character, residents would need to act fast.

Sally Goodrich, an early member of Hingham’s Conservation Commission, led the effort to create the Hingham Land Conservation Trust in 1972. The Hingham resident was concerned that open spaces, especially those with wetlands and streams important to the health of the town’s watershed and the Weir River might be threatened by a development push. After learning how land trusts elsewhere in Massachusetts worked as independent conservation stewards, Goodrich brought together founding board members with similar concerns—some who owned parcels they wanted to conserve as open spaces for future generations.

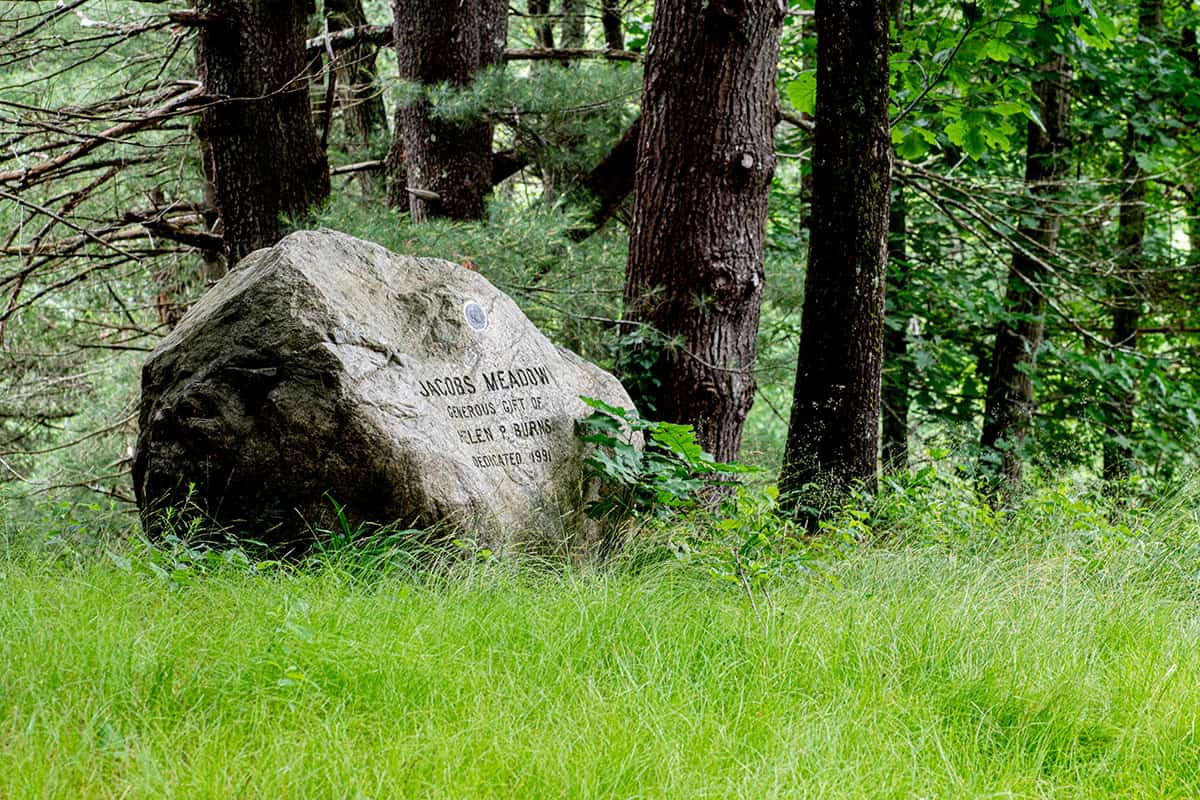

“We’re proud to be celebrating 50 years as an important conservation organization in Hingham,” says Eileen McIntyre, who was appointed HLCT board chair in 2019. “We stand on the shoulders of giants. Just last year we paid tribute to the late Helen Burns, a founding board member whose gifts of land to the HLCT and to the Hingham Conservation Commission created Jacobs Meadow – a 50-acre conservation area and parkland opened in 1991.”

Today, in addition to some smaller wetland parcels, the trust owns three properties accessible to the public: Eel River Woods (a gift of the late Mary Niles) and Whortleberry Hollow (a gift of the late Suvia Whittemore) – both off Cushing Street, along with Jacobs Meadow – entrance behind the Wilder Memorial Building on Main Street, a total of 65 acres. The HLCT also holds conservation restrictions on 118 acres, annually surveying and inspecting those lands for environmentally sensitive care.

“The trust’s founders focused on three main goals,” says McIntyre, “enhancing neighborhoods through gifts of land; holding restrictive covenants preserving land for recreational or open space uses; and working with the town to develop and recommend plans for open space. Today, the mission has evolved.” Much land in Hingham now has been saved or protected by conservation restrictions. Hingham voters’ approval in 2001 of a Community Preservation Act surtax, in part to fund acquisition of parkland, has been helpful too. One example: in 2017 Hingham town meeting approved use of CPA funds for the Town to acquire the Lehner Conservation Area—50 acres adjacent to Jacobs Meadow in the heart of our watershed.

“The trust’s role now is more focused on education and collaborative outreach to foster appreciation of open space,” says McIntyre. “We also want to help the community understand the local impact of climate change.” In 2020 the HLCT led a collaborative effort with the Bare Cove Park Committee, the local chapter of Wild Ones, a native-plants-focused organization, and local volunteers to create a native pollinator garden at Bare Cove Park. The goal is to allow visitors to observe how pollinator gardens not only are helpful for the ecosystem but create natural beauty, and once established, survive without watering.

In anticipation of its 50th anniversary this year, the trust began planning additional initiatives, and this May, at their annual meeting, they announced three new ventures. First, the trust is creating an online tool, called “50 Walks,” to more easily locate open spaces to enjoy in Hingham. This interactive guide, developed by Kidston, is available on the group’s website and allows residents and visitors to select a walk that meets their needs, whether they are interested in a rigorous hike, are walking with children or dogs, or have limited mobility.

Secondly, thanks to a generous bequest from the estate of founder Sally Goodrich, the trust has created a fund, enhanced through the generosity of current and former HLCT board members and longtime supporters, enabling the trust to begin awarding annual environmental research grants. Universities, town conservation departments, and nonprofit organizations that can define and execute an environmental research project for Hingham or surrounding towns on the South Shore can apply for a grant of up to $5,000. Information about how to apply for a grant will soon be available.

Lastly, the trust is digitizing its “Parklands for the Public” open space map of Hingham. This popular map, first printed in 1982, is being updated using GIS information and, at launch of the digital version this year, will include trail information on the trust’s three parklands. Over time, the digital map will be enhanced to provide additional trail level information for other parklands in Hingham. This initiative is funded by a gift from the estate of early supporter and board member, Mike Austin.

Meanwhile, ongoing trust activities continue. After a first-ever virtual walk last spring, the group returned to in-person seasonal walks last fall. In October, walkers enjoyed a vigorous hike while learning about kettle ponds at the south Hingham woodland owned by the Weir River Water System. This April, while walking along the Weir River near Triphammer Pond, participants heard about the importance of herring runs to the local ecosystem.

“It’s a big year for us,” says McIntyre, who handed the chair gavel to Art Collins in May. Collins, who previously served as vice-chair, organized the trust’s Pollinator Garden Initiative and is leading the digital Parkland Map project. McIntyre, who will stay involved as leader of the Goodrich Environmental Research Grant program, adds, “It is wonderful to see the Trust attract new supporters, board members and volunteers to carry our conservation mission forward.”

For more information, visit hinghamlandtrust.org.