Bob Kennedy’s landscape paintings and vintage-style prints reflect a vibrant life along the coast.

By Lannan M. O’Brien — Photography by Jack Foley

"Lighthouses are like people,” says artist Robert (Bob) Kennedy. After many years of painting ocean views across the country and beyond, the Quincy native and Cape Cod resident has become adept at noticing the distinct characteristics of each lighthouse he encounters, much like the facial features of each person he meets. “Something in every one of them is different.”

It’s a fitting observation for an artist who dedicated his life to exploring and painting iconic coastal locales. Kennedy’s earliest childhood memories are of playing in the marshes and beaches of Quincy. “It was a great place to grow up,” says Kennedy, who fondly recalls delivering newspapers as a boy, with a bag that “must’ve weighed 60 pounds.” He also remembers lying about his age for the coveted position of “pin boy” at the old Wollaston Bowladrome (he was about three years shy of the required age of 16). The bowling alley, says Kennedy, was a popular spot for young men from the nearby Naval Air Station to try to impress their dates.

Kennedy has always had a passion for drawing and painting. Born during World War II, he was thrilled by the heroic images filling his comic books growing up, and in high school, he improved his compositions by illustrating them. His English teacher encouraged him to pursue the arts, and it wasn’t long after that he earned a scholarship to the Rhode Island School of Design.

It was an exciting time to be an artist in Providence, and Kennedy found himself fascinated by the characters and scenes on the city’s streets. Inspired by Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” he left school in his junior year to travel with his sketchbook and paints in tow. He became successful painting portraits for $5 apiece at the Santa Monica Pier in California. Then, rather than being drafted during the Berlin Crisis, he enlisted in the Army National Guard, continuing to sketch in the barracks of Fort Sill, Oklahoma, during his required six months of active duty.

Eventually, the coast called him home to New England and Kennedy opened his first art gallery on Beacon Hill in 1968, inside a 19th-century stable. It was there, often enjoying an afternoon beer with a friend and watching the traffic leave the State House at rush hour, that Kennedy befriended some of Boston’s best-known political figures (Governor Dukakis was known to wave to them from the back of his limousine, while stuck in that same traffic). Through the ‘60s and ‘70s, they hosted parties attended by Speaker Tip O’Neill, Mayor Kevin White, then-State Representative Barney Frank and others. When Rep. Frank ran for Congress, Kennedy made his campaign slogans featuring the now-familiar slogan, “Neatness isn’t everything.”

Reflecting on his days creating posters for political campaigns and local events at bars and coffee shops, Kennedy realizes that it may have been the start of his vintage-style artwork — now, most of which features scenes of coastal towns and beaches, reminiscent of old postcards. When he started making posters, he initially silkscreened them, but the process was laborious. With his artwork becoming increasingly popular, he decided to paint them instead, imitating the vintage style with opaque watercolors.

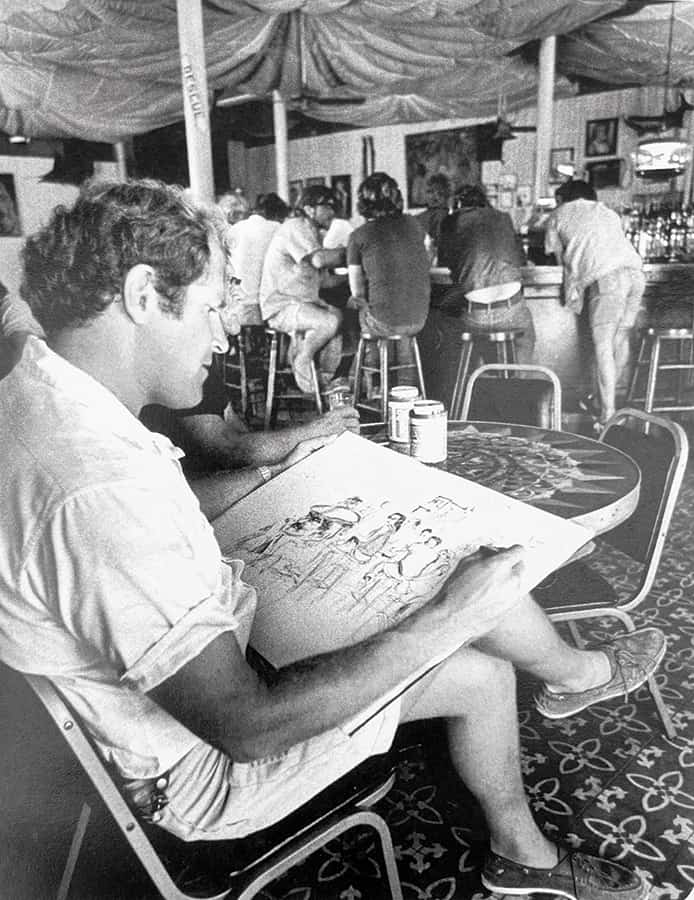

Thinking back to this time in his life, Kennedy credits himself and his friend, Hank, with starting the first iteration of Boston’s “booze cruise,” an idea sparked by the Long Wharf ferries rented for private events. They booked popular bands and filled the vessels with people, and according to Kennedy, “It was a smash.” He used the events to boost business for their local stomping ground, the Bull & Finch Pub (which later became Cheers Beacon Hill), through after-parties marketed with the help of Kennedy’s posters.It seems that everywhere Kennedy has lived or traveled has three things in common: a pub, a shoreline and a sketchbook. He spent more than 20 years in Key West, where he would often sketch at a local bar called Sloppy Joe’s that was once frequented by Ernest Hemingway. “You can’t get a sketchbook out without everyone in the place looking over your shoulder and starting a conversation,” he says. Kennedy would sit at a table, sketch the bar scenes and sell his paintings for the price of two beers. When asked how his earnings affected the work, he laughs and says, “They got better!”

Kennedy became well known for his colorful depictions of iconic streets and waterfront landmarks in towns across the East Coast, from Chatham to the Caribbean. By the mid ‘80s, there were 37 Kennedy galleries dotting the coastline from Kennebunkport to Key West. While some were run by Kennedy and his siblings, others were contracted out to local artists. These days, there is just one gallery remaining: Kennedy Gallery & Studios on Main Street in Hyannis, which has been operating since 1973. “I wanted to simplify my life,” Kennedy says. At 82, his goal is to work in the garden at his Barnstable home and sit on his new porch with his wife, Tina Kennedy. He hopes, however, to keep the last gallery open and in the family.

Just a few months ago, a man entered the gallery with artwork for framing. It was a 1977 scene of Sloppy Joe’s he bought from Kennedy at the bar. “I said, ‘I remember this one,’” and his memory came into focus when he noticed the beer and cigarette stains on the paper. That night, his father was sitting beside him as he worked. “Pop knocked over one of the beers. I had just finished a drawing, and the second I put it down, I said, ‘Oh, Jesus,’” he says, recalling his father’s habit of resting his cigarette on the edge of the table.

Many of Kennedy’s paintings have colorful stories associated with them, from his bold prints of Nantucket and Provincetown to his most recent vintage-style painting of Scituate Lighthouse. Captured in his signature style, it’s a unique perspective of the South Shore that is infused with an undeniable sense of place.